Reach your S.M.A.R.T. Goals with D.U.M.B. Habits

Halfway Habits

As we turn the corner on the year, I’m realizing I’ve not moved the needle on some of my goals. Sometimes they arise in the form of bothersome afterthoughts or nagging reminders; these resound from the shrillest register of my mother’s voice, running something like: “Remember how you said you wanted to test for your belt in jiu-jitsu?”, “When are you going to have that garage sale again?”, “Is the basement clean yet?” Other times, they ominously hang over my head like Sword of Damocles or a guillotine; the longer they remain unfinished, the more the suspense becomes unbearable. Coalescing from and dissipating back into a general miasma of dread, these more foreboding hauntings tend to address me in that ghastly, tremulous voice Jacob Marley once used to address Scrooge: “Boooo…. lose 40lbs by Christmas… Oooo….”

On the other hand, I’ve accomplished several of my goals well ahead of schedule. I’ve fulfilled a childhood dream of busking in the streets; I’ve surpassed my reading goal of thirty books before even hitting the halfway mark in the year; and—as you can see—I’ve succeeded in starting a blog. But why did these goals get done? Why not the others? It’s not that I was any more resolved in these resolutions than the others.

Many in the corporate world or productivity sphere will tell you that your goals need to be “S.M.A.R.T.”: Specific, Measurable, Actionable, Realistic, and Time-bound. But these goals are often easily and enthusiastically suggested, only to be put off or forgotten until the deadline sneaks up on us. On the contrary, as far as I can see, the only factor uniting all the goals I have achieved is that I almost didn’t think about them at all.

Rather than thinking about how I was going to do them, I just did them. As I mentioned in a recent post on Taoism and hesychasm, sometimes not doing (wu wei) or just doing things dispassionately (ἀπάθεια) is the key to the thing getting done. Formulating goals keeps me in my head, and all that planning makes it less like likely I’ll get anything done. All that thinking gets in the way of doing.

Frankly, goals are not enough. They need habits, and those habits are the best when they’re D.U.M.B. Here’s what I mean by that:

D: Daily

While goals need to be achieved only once, habits must be done regularly. Many goals have been achieved and lost because people didn’t have the habits to sustain them: many have lost mountains of weight only to regain it back after attaining the body they wanted; many have excelled in their careers and amassed reputational or financial gain, only to squander it after a season of resting on their haunches. If you don’t sustain your habits, you will lose your successes.

Time is one place where S.M.A.R.T. goals often drop by ball. When people chose a deadline in accordance with the Time-bound principle, they often tend to choose one comfortably far enough way from the present. The goal will be achieved “someday.” But that leaves open the question: what must we do today?

Habits are what we do everyday. And what we do everyday, defines who we are. As Annie Dillard wrote in The Writing Life, “How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.” Thus, readers read everyday. Writers write everyday. Parents parent everyday. Living people are alive and dead people are dead everyday. Likewise, you should work toward your goals everyday. Even when a goal has been achieved, it must be maintained everyday. Unlike a goal, habits don’t have a deadline. In that sense, you could say, they’re timeless—they’re eternal.

Imagine who you’d be when you achieve your goal. Let’s say you want to be more athletic and fit. What does that person do everyday? Maybe they run a mile everyday. Maybe they go to the gym everyday. Maybe you can’t do either of those yet. At the very least you might notice things you can do: they put on their running shoes everyday, they drink water everyday, they go to bed at the same time everyday. Whatever habit you chose, pick something you can do everyday. Then do it everyday.

U: Unassuming

Just as the temporality of our lives is made out of our mundane days, the significance of our lives is made in large part by our small, unnoticed, and often neglected actions. While goals often seem unsurmountable, our daily actions often seem insignificant. And that’s right. In isolation, a small action is a small action. But taken as a whole, many small actions have a cumulative effect, a synergetic force, a momentum that is more than any one significant action could hope to be on its own. As Bruce Lee once said, “I fear not the man who has practiced 10,000 kicks once, but I fear the man who has practiced one kick 10,000 times.” One unassuming habit can become quite a formidable skill over time.

The greatest reason for this, is that humans are living organisms. We grow. But what we call “growth” is actually our life healing itself in response to the stressors it experiences. When we lift weights, we tear muscle fibers and the body heals itself by growing back stronger, with more muscle fibers than it started with. This “mechanism of overcompensation” or “post-traumatic growth” grounds all of Nassim Taleb’s work in Antifragile, where he describes how we can benefit from disorder and volatility. Nietzsche also distills this logic in his famous maxim from Twilight of the Idols: “What doesn’t kill me, makes me stronger.” Small efforts trigger big growth.

For example, one of my habits is: “Read one page a day.” This utterly unassuming, unimpressive habit brings my eyes to a book every day, and (as noted above) we need to make our habits small enough that they can be done daily. So don’t bite off more than you can chew. Essentially, choose the least you can do—and then ask, “How I can do less?” The “minimum viable dose” and “the least we can do” are both less than we usually think.

In my case, one page is so small that I don’t even have to think about it (see M below); one page is as close to nothing as I can get (see B below). Once I’m there and I read that one page, the mechanism of overcompensation takes over and I often read a lot more after that. Because the bar is set so laughably low on my reading habit, it’s almost harder for me not to do it. Rig it to win it.

M: Mindless

Habits are what you do when you’re not thinking. Most of what we find in our lives and our work is done “out of habit.” When things are uneventful and running smoothly, good habits are probably at work. Sometimes bad habits are at work as well, but that just proves the point—all habits are mindless. By and large, we don’t know what we’re doing or even why we’re doing it. Most of life, pace Socrates, will always remain unexamined.

Thinking and doing are mutually exclusive activities. More precisely: thinking about doing is mutually exclusive with the doing itself. While the curation of a to-do list and assembly of plans takes mental effort, most of the actual tasks on those lists and in those plans can be done without thinking. Let’s substitute the to-do lists with sheet music or chord charts for a moment. Once I heard Kenny Werner, author of Effortless Mastery, discuss the tension between the pianist’s mind and hands like this: “Our hands can play faster and better than we can tell our hands what to play.” The hands can play faster and better when the mind doesn’t get in the way. With all of its theory and proscriptions, the heavy-laden mind is too slow to be helpful in the moment. Likewise, our habits can happen faster than it takes us to think about them.

Unfortunately, there are so many questions that keep us busy making our plans rather than doing our tasks. Given the choice between wondering about an action and doing an action, most of us chose the wondering; nature abhors a vacuum, and the mind detests uncertainty. If there are too many moving parts and open questions in a habit—what should I wear; what should I eat; what should I say; how long should I go; when should I leave; how long should I work—the mind’s endless rationalizations will stalls the body from moving and we’ll get nothing done. Thinking adds friction.

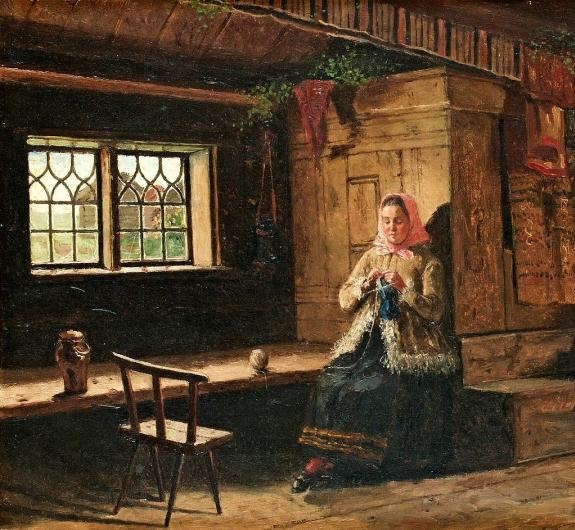

Before beginning, knitters might think about which the pattern of knots to use, but after that their hands move for hours at time without needing to think. In these leisurely hours without any mental demands, the mind can unwind; the repetitive working of the needless creates a paradoxical balance of mindfulness and mindlessness. Then the knitter’s attention can simply enjoy the dance of hands and yarn. To these knitter’s knitting’s an art, not a chore. Likewise, people who enjoy the gym don’t look at the gym as drudgery: their minds aren’t bothered with the tinkering with machines or techniques. The closer they get to the gym, the more they turn off their brains and just do the habit. Since our minds are so overstimulated with thinking and stressing these days, I think this self-forgetting mindlessness is one of the most important qualities to cultivate in our habits—and life itself, for that matter.

You’ll know you have a habit when you don’t think about whether or not you’ll do something. Ideally, you’d notice that you’ve already done it. Habits should almost be retrospective. Simplify the habit so there isn’t any deliberation, reflection, or mental effort required. By making our habits daily, we’ve removed the question of when we should do them. By making our habits unassuming, we removed the question of how much we should do. What other questions can we answer once and remove forever?

To revisit the example above: if we want to be healthy and athletic, maybe we need to eat the same food every week, maybe we need to do the same workout every week, maybe we need to buy several of the same clothes so we always have the same outfit ready for the gym (maybe we should turn laundry into a D.U.M.B. habit). Relentlessly reduce questions and uncertainty into your habits. However you do it, remove thinking and remove friction. Set it and forget it. Make the habit mindless.

B: Binary

By all means, dream up your goals in as many brilliant colors as your imagination can muster, but make your habits black and white. Our habits must starkly ask us: Did you do it? Yes or No? They don’t care about excuses, justifications, reframing, or any other rationalization; they just want to know if the work was done. Banish words like “mostly,” “kinda,” “a bit,” “well no, but…” from your vocabulary. Instead, “Let your ‘Yes’ be ‘Yes,’ and your ‘No,’ ‘No.’ For whatever is more than these is from the evil one.” (Matt 5:37).

Every principle in D.U.M.B. covered so far has been honing the habit into a binary. Whereas some people want to do something a couple times a week, a couple times a month, or an even more vague “here and there,” we simply said, “No. Daily. Every single day.” Now, it’s a binary. Likewise, when we made our habit Unassuming, we boiled it down to the smallest action we could do everyday; in the case of reading, there’s one page or none, and it doesn’t get more binary than 0 or 1. This also keep things Mindless, because we don’t have to think about “partially” doing our habits or doing them “in a way.” Again, running counter to all of this murky reflection, our habits ask: Did you do it? Yes or No? So feel free to let your goals be essay, but make your habits true or false. All or nothing. Habits are binary.

D.U.M.B. in Sum

No goal can be achieved without habits. Goals focus on what you want to achieve; habits tell us how you work to achieve them. Goals have plans; habits have processes. Goals involve discussion, debate, and clarification; habits do their work in silence. Goals are smart, habits are dumb.

D for Daily: Chose a habit you can do every single day.

U for Unassuming: Distill the habit down to the smallest possible actions.

M for Mindless: Remove uncertainties (questions and variables) from your habit.

B for Binary: Make your habit a Yes or No, Done or Not Done.

Links

Annie Dillard, The Writing Life

Nassim Taleb, Antifragile

Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols

Kenny Werner, Effortless Mastery

This was excellent! Thanks, Sam!

Thanks, Fr. Glad you enjoyed it.